Now hiring!

Moving assets between Ethereum and Starknet today is a multi-step process. You bridge, you wait, you swap, you pay gas twice, you hope nothing fails along the way. By the time you're done, you've aged a little and your tokens have taken a scenic route through half the internet.

Open Intent Framework for Starknet (OIFS) changes this. One signature, no gas, tokens arrive in seconds.

But what exactly is OIFS, and why does it matter for the Starknet ecosystem?

Whether you're a developer building cross-chain applications, a solver looking for MEV opportunities, or just someone tired of bridge UX, this post will walk you through everything you need to know about this implementation that's bringing intent-based execution to Starknet.

Before diving into OIFS specifically, it's worth understanding the ecosystem it's part of.

The Open Intents Framework launched in February 2025 as a collaboration between the Ethereum Foundation, Hyperlane, and Bootnode. Over 30 teams are backing it, including Arbitrum, Optimism, Polygon, ZKsync, and Scroll.

The framework is built on ERC-7683, a standard co-authored by Uniswap Labs and Across that defines how cross-chain intents should be structured and executed. Think of ERC-7683 as the common language that lets different intent systems talk to each other and solvers built for one implementation can work with others.

OIFS extends this framework to Starknet, making it the first implementation connecting Cairo VM with the ERC-7683 ecosystem.

Traditional cross-chain transfers require you to specify how to do something: approve this contract, call this bridge, wait for finality, execute this swap. Each step is your responsibility, and if one fails, you're stuck troubleshooting.

Intents flip this. You specify what you want: "I have 100 USDC on Ethereum, I want 95 USDT on Starknet." That's it.

The actors who make this happen are called solvers. Solvers are specialized participants who:

You sign a message. The solver does everything else. As one developer put it: "I went from dreading cross-chain transfers to forgetting they were even cross-chain."

Let's trace a real swap: 100 USDC on Arbitrum → 95 USDT on Starknet.

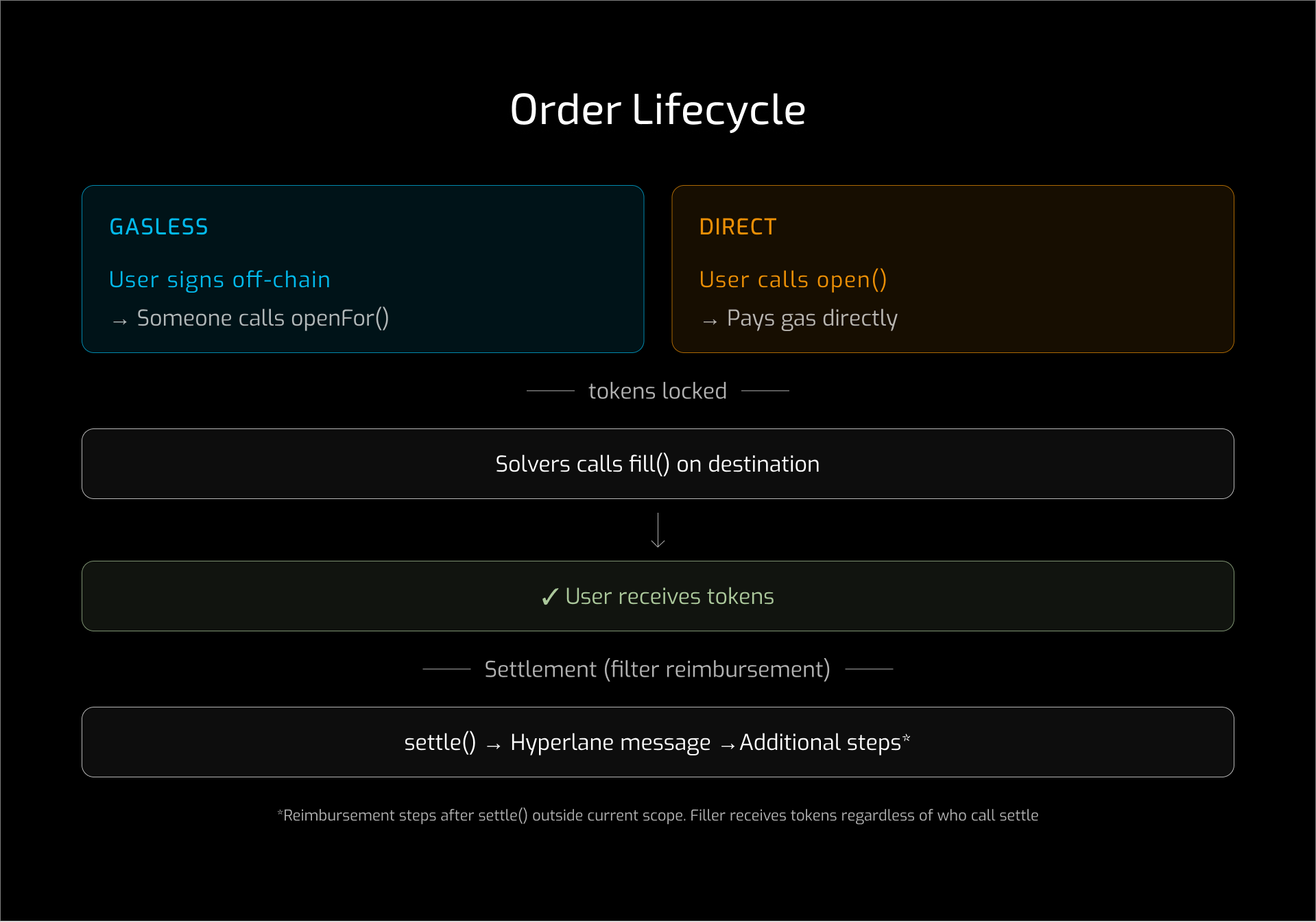

You create an order specifying what you're giving (100 USDC on Arbitrum), what you want (95 USDT on Starknet), where to send it, and a deadline. There are two ways to open an order:

openFor() with your signed order to open it on your behalf.open() directly on the contract yourself. This requires a transaction and gas, but doesn't need anyone to submit for you.

Whether opened via openFor() or open(), the contract:

openFor, direct transfer for open)Open event that solvers can see

Your tokens are now locked. The clock is ticking toward the fill deadline.

The solver calls fill() on the Starknet contract, transferring 95 USDT directly to your Starknet address. This is where your experience ends. You signed once, waited maybe 10-60 seconds, and received your tokens. Everything after this is solver housekeeping.

The solver now needs to collect the 100 USDC they're owed. They call settle() on Starknet, which dispatches a message through Hyperlane to Arbitrum: "Order X was filled, release the locked tokens."

When Arbitrum receives and verifies this message, it releases the 100 USDC to the solver who filled the order.

Note: The filler and the one who calls settle can be different—if Bob fills the order and Charlie settles it, Bob still receives the USDC since he was the filler.

This isn't theoretical. Here's actual transactions on testnet:

Arbitrum → Starknet (complete flow):

Starknet → Ethereum:

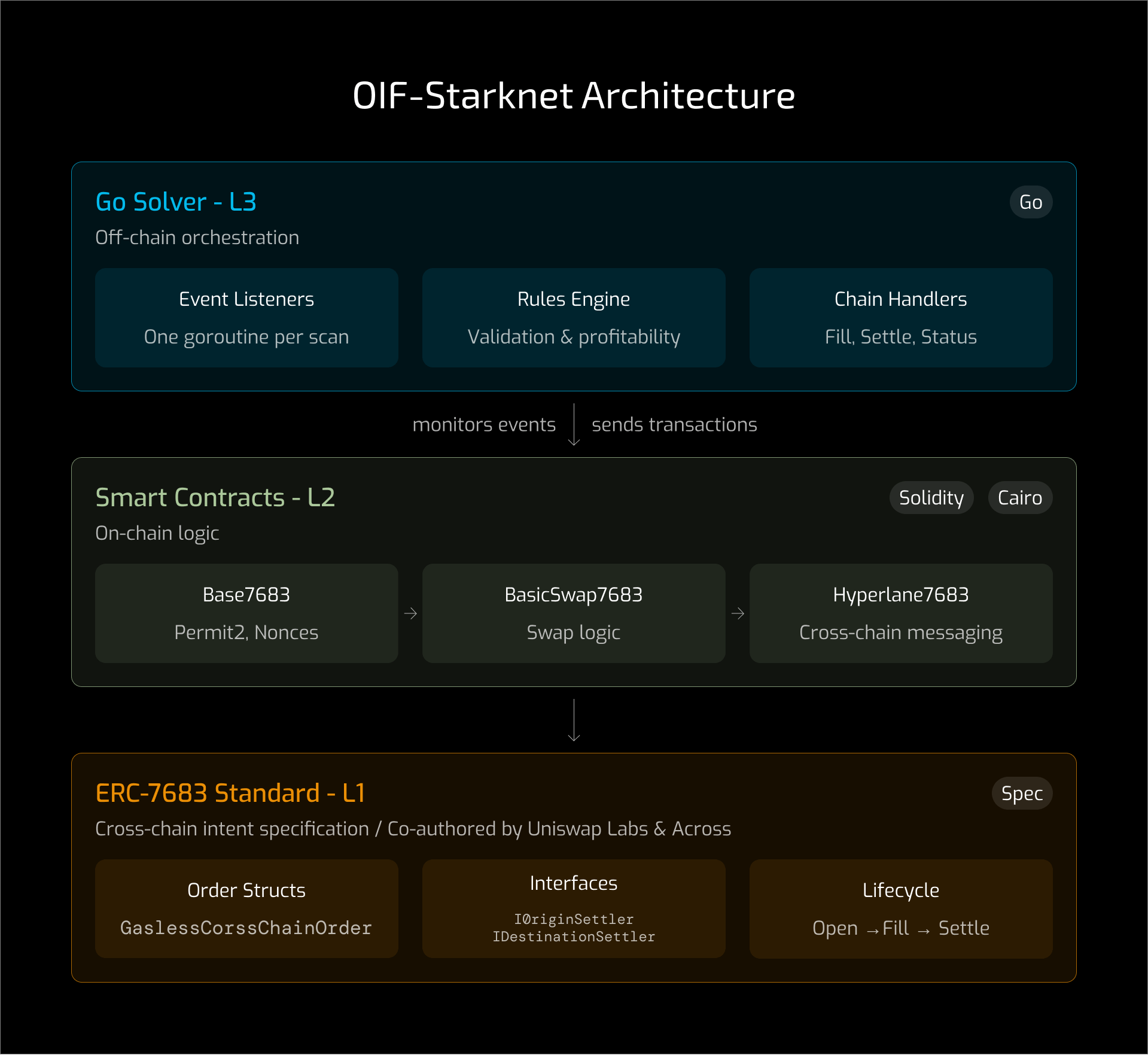

OIFS is built in three layers, each with a specific responsibility.

This defines the rules everyone follows. At its core, ERC-7683 specifies two interfaces that contracts must implement:

IOriginSettler which runs on the chain where users lock their tokens. It handles open() (lock tokens and emit the order), settle() (release tokens to solver after successful fill), and refund() (return tokens to user if order expires unfilled).IDestinationSettler runs on the chain where users receive tokens. It handles fill() (solver delivers tokens to user) and verifies that incoming settlement messages are legitimate.The standard also defines order structures. A GaslessCrossChainOrder contains everything needed to execute a swap: input token, output token, amounts, recipient address, deadlines, and the destination chain. This gets resolved into a ResolvedCrossChainOrder that includes fill instructions for solvers.

Why does this matter? Because any solver that understands ERC-7683 can fill orders from any compliant system. A solver built for Across can theoretically fill OIFS orders. Liquidity and infrastructure become shared rather than siloed. This is the difference between every bridge having its own isolated solver network versus a unified market where solvers compete across implementations.

Contracts live on both EVM chains and Starknet, following the same logical structure:

Base7683 is the foundation. It implements the core ERC-7683 interfaces, integrates Permit2 for gasless token approvals, and manages nonces to prevent replay attacks. When a user signs an order, the nonce gets marked as used and if it tried to submit the same signature twice, the transaction reverts. Base7683 also tracks order status (opened, filled, settled, refunded) and stores the order data needed for settlement verification later.Base7683 to implement single-token swap logic. This is where _fillOrder() actually transfers tokens from solver to user, where _settleOrders() releases locked tokens to solvers after verification, and where _refundOrders() returns tokens to users for expired orders. It's "basic" because it handles one input token for one output token hopefully future implementations could support multi-token swaps or more complex order types._dispatchSettle() and _dispatchRefund() which encode messages and send them cross-chain through Hyperlane's mailbox contracts. On the receiving end, _handle() processes incoming messages and calls the appropriate settle or refund logic. This is also where gas payment for cross-chain messages gets quoted and paid.

On Solidity, this is standard inheritance where each contract extends the previous one. On Cairo, Hyperlane7683 uses component injection, which is Cairo's approach to composition. The logic is equivalent, but Cairo doesn't have inheritance in the traditional sense, so the base contracts get injected as components that Hyperlane7683 delegates to.

We ported Permit2 to Cairo to keep the signing experience consistent across chains. A user signing an order on Ethereum and a user signing on Starknet go through the same flow as EIP-712 style typed data signatures that bind the token approval to the specific order. More on why we didn't use Starknet's native SRC9 later.

The solver is a Go application running off-chain that orchestrates everything.

Open events. Each chain gets its own goroutine, so the solver can watch Ethereum, Arbitrum, Optimism, Base, and Starknet simultaneously without blocking. When an Open event fires, the listener parses the order data and passes it to the intent handler. The listeners also track the last indexed block and persist it to disk and whenever the solver restarts, it picks up where it left off rather than re-processing from genesis.ChainHandler interface with three methods: Fill() to deliver tokens on destination, Settle() to claim reimbursement from origin, and GetOrderStatus() to check order state. The EVM handler and Starknet handler have different implementations (different RPC calls, different encoding) but expose the same interface. This is what makes adding new chains straightforward and implement the interface and the rest of the solver just works. The solver also handles nonce management for transaction submission, retry logic for failed transactions, and concurrent execution across multiple orders. It's designed to run continuously as infrastructure, not as a one-off script.

Building cross-VM infrastructure isn't just about calling contracts on different chains. Here are the interesting challenges we solved.

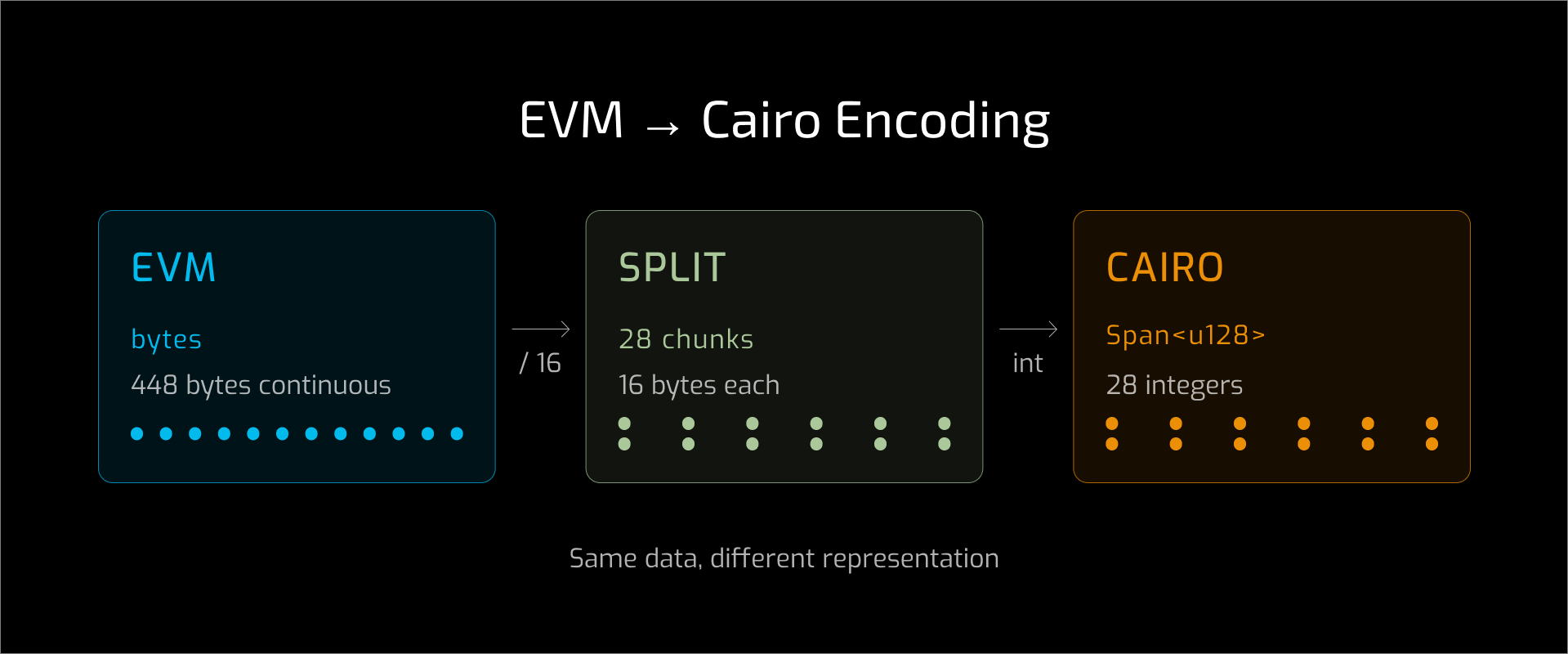

EVM and Cairo speak different languages at the byte level. This is like trying to fit an elephant into an Aston Martin, except the elephant is 448 bytes of order data, and the Aston Martin only understands field elements.

EVM contracts work with bytes which are arbitrary byte arrays. Cairo does have a native ByteArray type, but OIFS uses Alexandria's Bytes type which internally uses a u128 array.

The solution: split 448 bytes into 28 chunks of 16 bytes each, encode each chunk as au128integer, pass asSpan<u128>to Cairo. The Go solver handles this conversion, and Cairo decodes it back on the other side. Same data, different representation.

EVM uses bytes32 for order IDs which is a 256-bit hash. Cairo represents 256-bit numbers as u256, which is a struct with low: u128 and high: u128. The solver splits every order ID into low and high components when calling Cairo contracts.

Starknet has SRC9 (Outside Execution) which is a native way to delegate execution. We considered using it instead of porting Permit2 (which was significant work).

The issue was that our flow involves two accounts. The user signs, but the solver submits. SRC9 is designed for delegating execution within a single account's context not two different accounts.

Whereas Permit2's model fits our cross-account flow. The user signs a message that approves a specific token amount, binds that approval to a specific order (via "witness" data), and has an expiration. If the solver tries to modify the order, the witness data won't match, the signature verification fails, and the transaction reverts.

Using Permit2 also keeps the experience consistent as the same signing flow whether you're on Ethereum, Arbitrum, or Starknet.

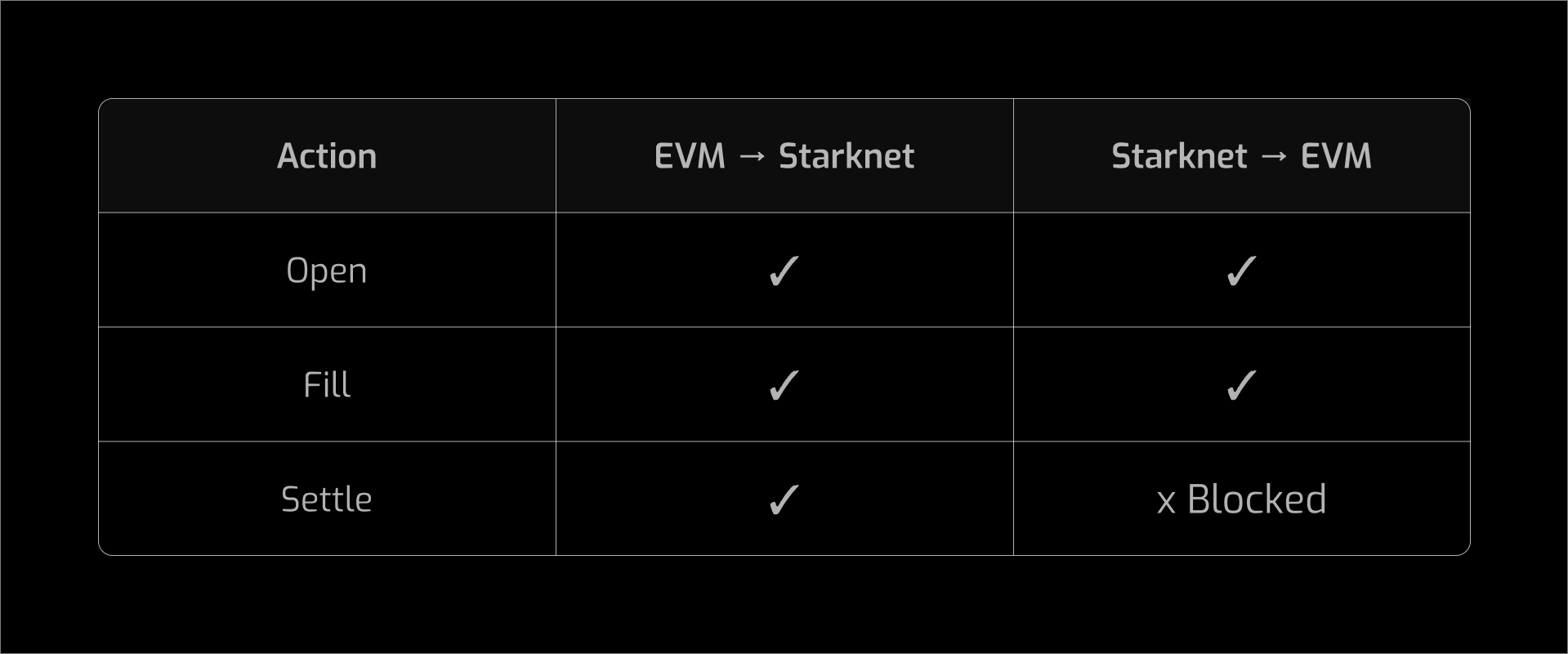

Here's what works and what doesn't:

EVM → Starknet works through the settle step. Users get tokens, and settle() is called to dispatch the settlement message.

Note: the actual reimbursement to the solver requires additional steps after settle() that were outside the scope of this implementation.Starknet → EVM fills work, but settlement is blocked. Users still receive tokens on the EVM side—the fill completes successfully. What's broken is the solver claiming reimbursement from Starknet afterward.

Two separate issues:

Important: This only affects solver reimbursement. Users bridging from Starknet to EVM still receive their tokens as soon as the fill completes. The limitation means solvers take a loss on Starknet → EVM orders until these issues are resolved.

Hyperlane7683 and Permit2 are deployed and operational on:

With the solver configured to fill immediately when the Open event is detected (0 confirmation blocks), orders complete in 10-60 seconds depending on network conditions.

In production, solvers would likely wait for some confirmations before filling, which adds latency but reduces reorg risk. Mainnet would probably be on the slower end of this range.

# Clone the repo

git clone https://github.com/NethermindEth/OIFS

cd OIF-starknet/solver

# Configure environment

cp example.env .env

# Edit .env with your RPC URLs and private keys# Build and run

make build

./build/solver

The solver will start listening for Open events across all configured chains. Each chain listener runs as an independent goroutine, and backfilling handles any missed events during downtime.

The solver has a pluggable rules engine. You can add custom rules to filter which orders to fill—for example, only filling orders above a certain profit margin or from specific token pairs. Rules are composable and can be added without modifying the core solver code.

Each supported chain implements a ChainHandler interface with methods for Fill(), Settle(), and GetOrderStatus(). The solver handles event listening, routing, and state management—you implement the chain-specific logic. This abstraction is what makes adding new chains straightforward.

Short term:

Longer term: