Now hiring!

We have completed our work on mechanizing the semantics of the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) and the associated Yul intermediate language in the Lean proof assistant, focusing on the Cancun hard fork. This work was generously supported by the Ethereum Foundation grant entitled “Towards an Executable Formal Model of EVM and Yul in Lean”.

To make sure that our mechanization is trustworthy, we have taken great care to follow the official Ethereum Yellow Paper as well as test conformance against the Cancun tests that are available in the appropriate official Ethereum test suite. We believe that we have the most complete formal model of the EVM to date, passing 99.99% (22,330/22,332) of these Cancun execution tests.

Our formal model of EVM/Yul is open-sourced and is available for the Ethereum community at NethermindEth/EVMYulLean. This work presents a significant investment in the security of Ethereum and provides a foundation for future formal verification of smart contracts, execution clients, and zkVMs.

The remainder of this blog is primarily aimed at readers with prior familiarity with the EVM, the Yellow Paper, and interactive theorem proving. It focuses on design choices and semantic fidelity rather than serving as an introduction to Lean or Ethereum execution.

During the formalization process, we took the Yellow Paper as the original source of truth. However, as we started to test against the official test suite, it became evident that the behaviors expected by tests are at times different than those described by the Yellow Paper. In those cases, we either:

Therefore, in summary, we took the conformance test suite as the ultimate source of truth, and predominantly used KEVM to understand how to bridge the differences in expected behavior between the test suite and the Yellow Paper.

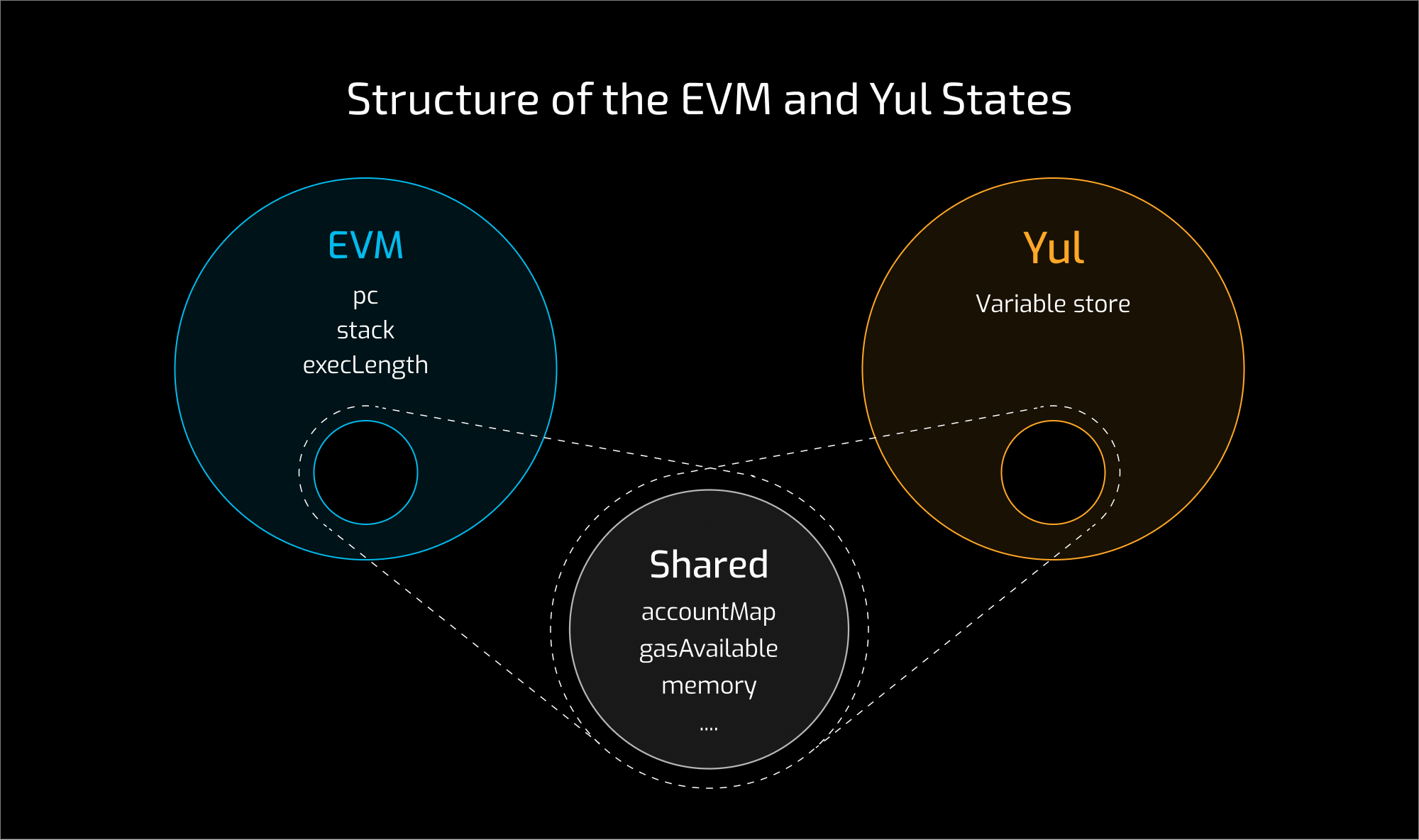

In order to be able to share the common components of EVM and Yul states across the two developments, we construct the states modularly.

First, we define two state components following the Yellow Paper:

/--

The `State`. Section 9.3.

- `accountMap` `σ`

- `substate` `A`

- `executionEnv` `I`

- `totalGasUsedInBlock` `Υᵍ`

-/

structure State (τ : OperationType) where

accountMap : AccountMap τ

σ₀ : AccountMap .EVM

totalGasUsedInBlock : ℕ

transactionReceipts : Array TransactionReceipt

substate : Substate

executionEnv : ExecutionEnv τ

blocks : ProcessedBlocks

genesisBlockHeader : BlockHeader

createdAccounts : Batteries.RBSet AccountAddress compare

/--

The partial shared `MachineState` `μ`. Section 9.4.1.

- `gasAvailable` `g`

- `memory` `m`

- `activeWords` `i` - # active words.

- `returnData` `o` - Data from the previous call from the current environment.

-/

structure MachineState where

gasAvailable : UInt256

activeWords : UInt256

memory : ByteArray

returnData : ByteArray

H_return : ByteArray

Next, we bring these two sets of state components together to form the state that will be shared by both EVM and Yul:

structure SharedState (τ : OperationType)

extends EvmYul.State τ,

EvmYul.MachineState

Finally, we add on top the EVM-specific program counter, the stack, and the execution depth counter, obtaining the full EVM state:

/--

The EVM `State` (extends EvmYul.SharedState).

- `pc` `pc`

- `stack` `s`

- `execLength` - Length of execution.

-/

structure State extends EvmYul.SharedState .EVM where

pc : UInt256

stack : Stack UInt256

execLength : ℕ

The Yul state, as we shall see shortly, comes with a Yul-specific variable store (that is, a finite partial mapping from variable identifiers to Yul literals) on top of EvmYul.SharedState.

The main EVM-related semantic definitions can be found in the Semantics.lean file. For example, the main step function can be found here. It fetches the next opcode to execute, then calculates the appropriate gas cost, and executes the instruction. Below is an excerpt of the code, annotated with explanations:

def step

...

(gasCost : ℕ)

(instr : Option (Operation .EVM × Option (UInt256 × Nat)) := .none)

:

EVM.Transformer

:=

...

match instr with

| .CALL => do

-- Names are from the YP, these are:

-- μ₀ - gas

-- μ₁ - to

-- μ₂ - value

-- μ₃ - inOffset

-- μ₄ - inSize

-- μ₅ - outOffsize

-- μ₆ - outSize

let (stack, μ₀, μ₁, μ₂, μ₃, μ₄, μ₅, μ₆) ← evmState.stack.pop7

let (x, state') ←

call gasCost evmState.executionEnv.blobVersionedHashes

μ₀ (.ofNat evmState.executionEnv.codeOwner)

μ₁ μ₁ μ₂ μ₂ μ₃ μ₄ μ₅ μ₆ evmState.executionEnv.perm

evmState

let μ'ₛ := stack.push x -- μ′s[0] ≡ x

let evmState' := state'.replaceStackAndIncrPC μ'ₛ

.ok evmState'

...

-- Instructions other than creates and calls

| instr =>

EvmYul.step

instr

arg

{ evmState with

gasAvailable := evmState.gasAvailable - UInt256.ofNat gasCost }

It is worth noting that we have factored out the semantics of all of the opcodes that have the same semantics in EVM and Yul into a separate EvmYul.step function, so that both semantics can make use of it seamlessly.

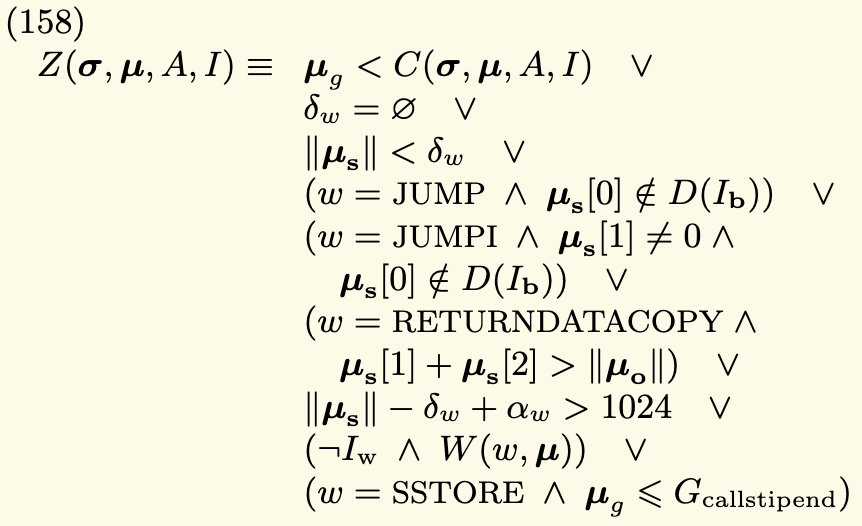

Importantly, to maintain eyeball closeness to the Yellow Paper, we also re-use the function names therein in our formalization. For example, the Z function, defined in equation (158) of the Yellow Paper, which handles exceptional halting, is defined in the Yellow Paper as follows:

Setting out nine cases in which exceptional handling can occur. In our formalisation, it is defined as follows:

let Z (evmState : State) : Except EVM.ExecutionException (State × ℕ) := do

-- Case 1

-- cost₁ corresponds to Cmem(μ_i') - Cmem(μ_i) of (328) of Yellow Paper

let cost₁ := memoryExpansionCost evmState w

if evmState.gasAvailable.toNat < cost₁ then .error .OutOfGas

let gasAvailable := evmState.gasAvailable - .ofNat cost₁

let evmState := { evmState with gasAvailable := gasAvailable}

-- cost₂ corresponds to the case split of (328) of Yellow Paper

let cost₂ := C' evmState w

if evmState.gasAvailable.toNat < cost₂ then .error .OutOfGas

-- Case 2

if δ w = none

then .error .InvalidInstruction

-- Case 3

if evmState.stack.length < (δ w).getD 0

then .error .StackUnderflow

-- Case 4

if w = .JUMP ∧ (notIn evmState.stack[0]? validJumps)

then .error .BadJumpDestination

-- Case 5

if w = .JUMPI ∧ (evmState.stack[1]? ≠ some ⟨0⟩) ∧ (notIn evmState.stack[0]? validJumps)

then .error .BadJumpDestination

-- Case 6

if w = .RETURNDATACOPY ∧ (evmState.stack.getD 1 ⟨0⟩).toNat + (evmState.stack.getD 2 ⟨0⟩).toNat > evmState.returnData.size

then .error .InvalidMemoryAccess

-- Case 7

if evmState.stack.length - (δ w).getD 0 + (α w).getD 0 > 1024

then .error .StackOverflow

-- Case 8

if (¬ evmState.executionEnv.perm) ∧ W w evmState.stack

then .error .StaticModeViolation

-- Case 9

if (w = .SSTORE) ∧ evmState.gasAvailable.toNat ≤ GasConstants.Gcallstipend

then .error .OutOfGas

-- Case 10: EIP-2677

if w.isCreate ∧ evmState.stack.getD 2 ⟨0⟩ > ⟨49152⟩

then .error .OutOfGas

-- No exception, computed gas cost

pure (evmState, cost₂)

For most of these conditions, there exists a clear eyeball correspondence with the paper definition, with the exception of the following two details:

The reader can easily find in the formalization the other main functions declared in the Yellow Paper just by looking up the appropriate function names (e.g., X, Ξ, Lambda, etc.). Importantly, the Ethereum state transition function, Υ (as introduced in (1) of the Yellow Paper), can be found here.

In our formalization, we delegate the execution of EVM pre-compiles to external, efficient Python or C implementations via Lean’s FFI interface.

We are able to test our mechanized semantics of the EVM against the official Cancun test suite, passing 22,330 out of the 22,332 tests. This %99.99 coverage makes our formal model, to the best of our knowledge, the most conformant formal model of the EVM. The semantics of the two remaining tests is unclear and potentially non-deterministic, and to understand this we have opened appropriate pull requests here and here.

Assuming the EthereumTests submodule has been checked out, the full test suite can be run using:

lake test -- <NUM_THREADS> 2> out.txt

where <NUM_THREADS> is the number of threads running conformance tests in parallel (with default 1). We also recommend redirecting stderr into a file (e.g., out.txt) to not pollute the output.

Yul is an intermediate programming language for Ethereum smart contracts. It was designed to be a common language that can be used by various high-level languages and serves as an optimization layer in the compilation pipeline from these high-level languages to EVM bytecode. Yul has a simple, structured syntax that makes it easier to perform manual optimizations and reason about gas costs compared to working directly with EVM assembly, while still providing low-level control over contract execution.

We straightforwardly formalize the syntax of Yul as a mutually inductive definition covering function definitions, expressions, and statements as follows:

mutual

inductive FunctionDefinition where

| Def : List Identifier → List Identifier → List Stmt → FunctionDefinition

deriving BEq, Inhabited

inductive Expr where

| Call : (PrimOp ⊕ YulFunctionName) → List Expr → Expr

| Var : Identifier → Expr

| Lit : Literal → Expr

inductive Stmt where

| Block : List Stmt → Stmt

| Let : List Identifier → Option Expr → Stmt

| ExprStmtCall : Expr → Stmt

| Switch : Expr → List (Literal × List Stmt) → List Stmt → Stmt

| For : Expr → List Stmt → List Stmt → Stmt

| If : Expr → List Stmt → Stmt

| Continue : Stmt

| Break : Stmt

| Leave : Stmt

deriving BEq, Inhabited, Repr

end

The semantics of Yul is formalized as follows. First, we define the state on which Yul programs operate as:

/--

A jump in control flow containing a checkpoint of the state at jump-time.

- `Continue`: Yul `continue` was encountered

- `Break` : Yul `break` was encountered

- `Leave` : EVM `return` was encountered

-/

inductive Jump where

| Continue : EvmYul.SharedState .Yul → VarStore → Jump

| Break : EvmYul.SharedState .Yul → VarStore → Jump

| Leave : EvmYul.SharedState .Yul → VarStore → Jump

/--

The Yul `State`.

- `Ok state varstore` : The underlying `EvmYul.SharedState` and variable store.

- `OutOfFuel` : No state, denoting we have run out of fuel (required for proving termination in Lean).

- `Checkpoint` : Used for restoring a previous state due to control flow.

-/

inductive State where

| Ok : EvmYul.SharedState .Yul → VarStore → State

| OutOfFuel : State

| Checkpoint : Jump → State

noting that the use of OutOfFuel allows easier reasoning about termination in Lean and does not get triggered in practice, whereas the use of Checkpoint allows for delayed reasoning about execution errors. These choices can both be made differently. Also, note how the Yul state includes the shared EvmYul.SharedState state, together with a variable store, that is, a finite partial mapping from program variables to Yul literals.

The interpreter is then defined in Interpreter.lean, through a series of mutually recursive functions that evaluate expressions (eval) and statements (exec).

As there are no official conformance tests available for Yul at the time of writing this blog, we have manually created a small test suite ourselves. These tests are defined here and can be executed by running:

lake exe yulSemanticsTests

There are certain aspects of our Yul formalization that require further work. In particular:

CREATE and CREATE2 opcodes, as these would require decompilation of the provided bytecode of the contract back into Yul;EXTCODESIZE, EXTCODEHASH, EXTCODECOPY, CODECOPY, and CODESIZE opcodes, as these have to inspect the bytecode of a contract;SELFDESTRUCT opcode.

We believe that this work presents a foundation on top of which numerous security-related efforts for Ethereum can be built. For example: